Autism and Other Common Developmental Conditions – Similarities and Differences

In an age where patients and families have a wealth of information at their disposal about diagnosis, ranging in quality from excellent to poor/misleading, remaining well informed as clinicians is more important than ever.

First and foremost, families usually want to know “what is going on with my child developmentally?” but beyond that they want to know “how can we make things better for them?”.

When we work in clinically referred populations, I like to point out to my students that developmental conditions (Autism, ADHD, intellectual disability, language delay, and a number of others) are ‘always on the table’. For example, although the general population rate of Autism is 1-2%, in mental health clinics the figure is likely to be more like 10-25%; and although the general population rate of ADHD is around 5%, in mental health clinics it can be more like 25-50%.

One of the hardest things about diagnosis is the fact that the symptoms of the various diagnoses often show considerable overlap. If you’re ever curious about the context in which diagnoses evolved, and the pressures felt by diagnosticians to find a ‘label’ that uniquely fits each possible syndrome, the book “Madness Explained” is an excellent if provocative read.

When lecturing students on diagnosis I sometimes play a fun game that I found on uQuiz, called “Goose or Duck?”. There are 11 pictures and you have to identify geese from ducks: you’d think that any preschooler could tell a goose from a duck, but it’s actually extremely difficult in some cases! After all, both have certain features in common: beaks, feathers, and webbed feet. But presumably (though I’m no zoologist) there are important differences also. Much the same with developmental diagnoses.

What are the ‘common features’ then amongst various diagnoses affecting children and adolescents?

Children, adolescents, and young adults often present with:

- social difficulties

- communication problems

- emotional dysregulation

- learning challenges

All of these can occur in Autism - but also commonly appear in ADHD, Intellectual Disability, and Language Delay for very different reasons.

This article breaks the problem down into:

- Core Autism features

- A breakdown of how each differential can appear similar to ASD, but also crucially which Autism features are not present

- The features that positively distinguish each condition from Autism

Core Features of Autism

Across ages, Autism is defined by two core domains, with onset in early development:

1. Social communication differences

- Reduced social reciprocity (back-and-forth interaction, sharing of interests, responding to others’ emotions)

- Difficulty using and reading non-verbal social cues (facial expressions, gesturing, body language, and eye contact)

- Difficulty adjusting communication to context, and in general, knowing and applying the ‘unwritten rules’ that make social interaction smooth and comfortable

- Peer relationships that are qualitatively different, such as a tendency towards social rejection/isolation or gravitating towards one or two ‘safe’ people

2. Restricted / repetitive patterns

- Repetitive/stereotyped movements, mannerisms, or speech

- Strong preference for sameness, rituals, and routine (and often marked distress when everyday conditions/routines change)

- Restricted or intense interests (i.e. typical interests of extreme intensity, or interests/collections that others without ASD wouldn’t usually share)

- Sensory sensitivities and sensory seeking (sounds, textures, tastes/smells, movement, lights) and sometimes reduced sensitivity (e.g. to temperature)

Here, the main point is that Autism is not just social difficulty or awkwardness, and it’s also not just getting upset when things change - it’s a constellation of differences and difficulties that work together to form an overall clinical picture.

Differential 1: ADHD vs Autism

Where ADHD can look like Autism

- Poor conversational turn-taking (e.g. info-dumping)

- Interrupting or talking excessively

- Missed social cues (see below though - largely due to inattention)

- Emotional dysregulation

- Peer difficulties (again, often for differing reasons)

- Sensory seeking or sensitivity/avoidance (especially in younger children)

This overlap is why ADHD is the most common mis- or co-diagnosis with Autism. To make matters more tricky, they do of course often co-occur (which we’ll cover towards the end).

Autism features you would NOT expect in ADHD alone

- Persistent difficulty understanding social meaning and applying theory of mind skills (i.e. once an ADHD-er has noticed a social cue they generally get it)

- Reduced social motivation is more common in Autism

- Deep need for sameness or rigid routines for their own sake (e.g. rather than the more ADHD style ‘I always carry a notebook in case I forget my tasks’)

- Restricted interests that dominate identity and defy attempts at redirection

- Social difficulties that persist even when attention is well supported

Features that distinguish ADHD from Autism

- Social mistakes are inconsistent not pervasive, and generally easily addressed

- Social understanding is intact when attention is engaged (e.g. they might miss social cues if they’re not paying attention in the right way, but they can easily understand their social errors/missteps once they tune back in)

- Strong imaginative play and humour is more characteristic of ADHD

- Flexible identity and interests: ADHD-ers often find it easier to pick up on their own info-dumping and adapt

- Impulsivity rather than rigidity in terms of habit preference

Anecdotal example:

I often tell clients and colleagues a useful example: you could equally well imagine a person with ADHD or a person with Autism talking all night about their new promotion at work, despite the fact that their friend sitting quietly in the group has just been fired from their job. However, the difference is that as soon as you remind the person with ADHD about this blunder they’ll be mortified and will instantly ‘get’ which social rule they broke. That’s not to say that the person with Autism wouldn’t get it at all, but it may have to be explicitly explained in some cases.

Differential 2: Intellectual Disability vs Autism

Where Intellectual Disability can look like Autism

- Delayed speech and language

- Immature social behaviour

- Difficulty with abstract social concepts

- Reliance on routine

- Limited peer relationships

Autism features you would NOT expect in Intellectual Disability alone

- Uneven cognitive profile (e.g. high reasoning + poor social insight), i.e. with intellectual disability the difficulties are generally across the board

- Social differences that exceed overall developmental level in Autism

- Circumscribed interests that are unusually intense

- Atypical social communication style (not just delay - e.g. the ‘erudite professor’ style is a qualitatively different form of social communication in Autism)

- Sensory reactivity disproportionate to cognitive level

Features that distinguish Intellectual Disability from Autism

- Global delays across all domains, not just social: and in general the social skills tend to match or exceed the mental age

- Interest range is limited but not idiosyncratic

- Communication difficulties reflect comprehension limits rather than social connection difficulties per se

- No distinct autistic social style: more likely to feel like a delay rather than a quirky social style

In summary:

ID presents as difficulty with independence and reasoning, whereas Autism if high functioning may present with high intelligence but profound social fatigue or misunderstanding; and lower intellectual functioning with Autism tends to co-occur with much more of the restrictive/repetitive behaviours.

Differential 3: Language Delay / Developmental Language Disorder vs Autism

Where Language Delay can look like Autism

- Late talking

- Difficulty expressing needs

- Reduced conversation

- Pragmatic (social language) weaknesses

- Frustration-driven behaviour

- Peer misunderstandings

Autism features you would NOT expect in Language Delay alone

- Reduced social interest or reciprocity

- Poor eye contact independent of language demand

- Restricted interests

- Repetitive behaviours unrelated to communication

- Sensory sensitivities as a core feature

- Difficulty understanding social intent once language improves

- Regressions in language functioning after skills have been established for a period are much more common in Autism - unless there’s also a Neurological presentation such as epilepsy

Features that distinguish Language Delay from Autism

- Strong non-verbal communication (gesture, eye contact, shared enjoyment)

- Social curiosity and engagement, stronger drive to connect and ‘make it work’ despite the speech delay

- Rapid social improvement as language develops

- Play skills are socially reciprocal: kids with language delays will usually find a way to connect and transcend linguistic communication

- Little or no insistence on sameness, nor fixed/restricted interests

In summary:

Language Disorder may show as academic or expressive difficulty, while social understanding is otherwise age-appropriate.

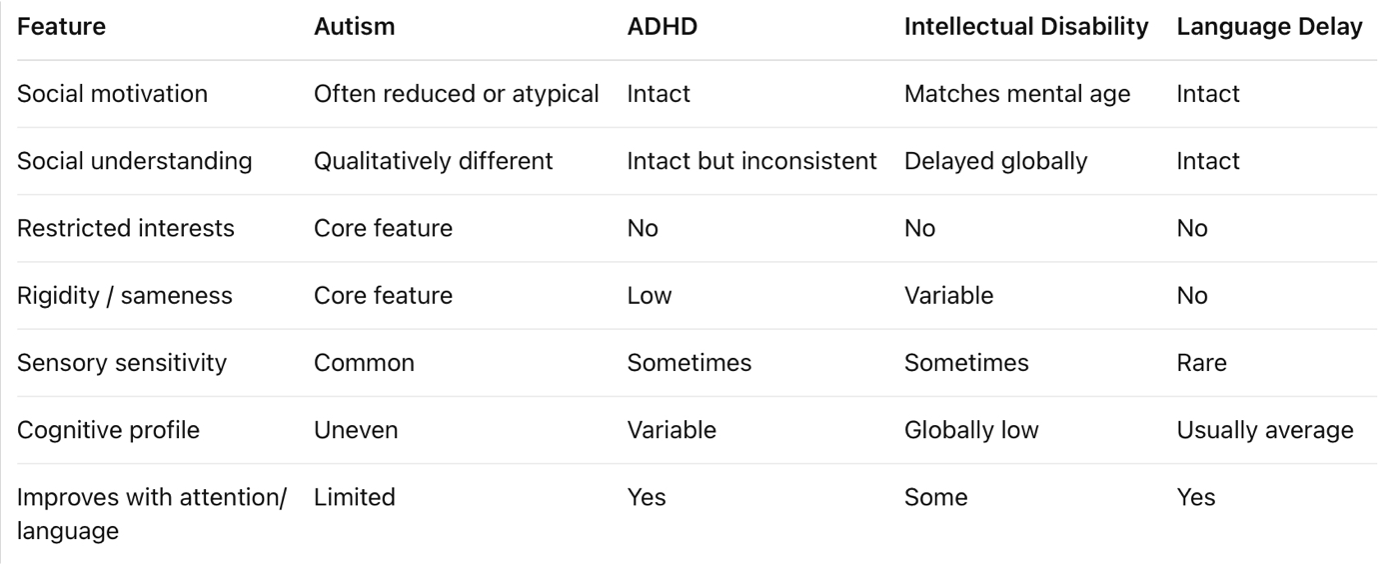

Side-by-Side Summary Table

A crucial final point: co-occurrence is common

These are differentials, not things that never co-occur (unlike the duck-goose situation, which I’m pretty sure are never both!).

So it is entirely possible, and in fact quite common, for a young person to have Autism as well as one or more of these other conditions:

- If a person has Autism, they have a 50-70% chance of also having ADHD; a 30-40% chance of having an Intellectual Disability; and 30-50% chance of a language disorder

Interestingly though, the stats are often not quite as high the other way around:

- If a person has ADHD, they have a 20-30% chance of also having Autism; if a person has an intellectual disability they have about a 30-50% chance of also having Autism; and if a person has a language disorder they have about a 10-30% chance of also having Autism

This is why high-quality assessment looks at:

- patterns, not checklists

- what is missing, not just what is present

- developmental history across time

⸻

Take-home message

Autism is not defined by difficulty or delay, but by a distinctive neurodevelopmental profile.

The most useful diagnostic question is often not:

“Do they have some autistic-like behaviours?” but also “What else could it be if not Autism, and what would else would we see if so” and sometimes even “Could it be multiple things?”